The Field Trip, 2024 - Modernism in New England and at ART

It was an early morning on June 6 for the ART Team. The office was closed but we had big plans for the day. It was field trip time!

Each spring the ART team likes to travel somewhere outside of our office to stretch our legs and to see something inspiring and out of the ordinary. If you don’t know about this tradition, you might first read last year’s Journal entry about our field trips, linked here. But then come back! Because in this entry we will be delving into the modernist sensations of New Canaan, CT, two of which we had the delight of visiting this June: The Eliot Noyes House, built in the 1950s, and the community center at Grace Farms, completed more recently in 2015.

New Canaan, CT

New Canaan is a relatively small suburban town about halfway between New York City and New Haven, a little over three hours from Boston. In the middle of the 20th century New Canaan would become a hub for modernist architects to experiment with their craft. Beginning in 1949, a group of alumni and colleagues of Walter Gropius at Harvard’s Graduate School of Design (called the “Harvard Five,” they included John Johansen, Marcel Breuer, Landis Gores, Philip Johnson, and Eliot Noyes) moved in to New Canaan. Once they landed, others followed. The result of this migration was arguably one of the most exciting periods of architectural idea exchange and modern design development of the 20th century in America. At some point there may have been as many as 120 modern houses in New Canaan. There may be 80 left today. A few of those remaining have become monuments to American mid-century modernism and to the architectural dialog of the time.

Fast forward to the 21st century. The modernist buildings of New Canaan continue to influence new designs in the region.

ART's Trip

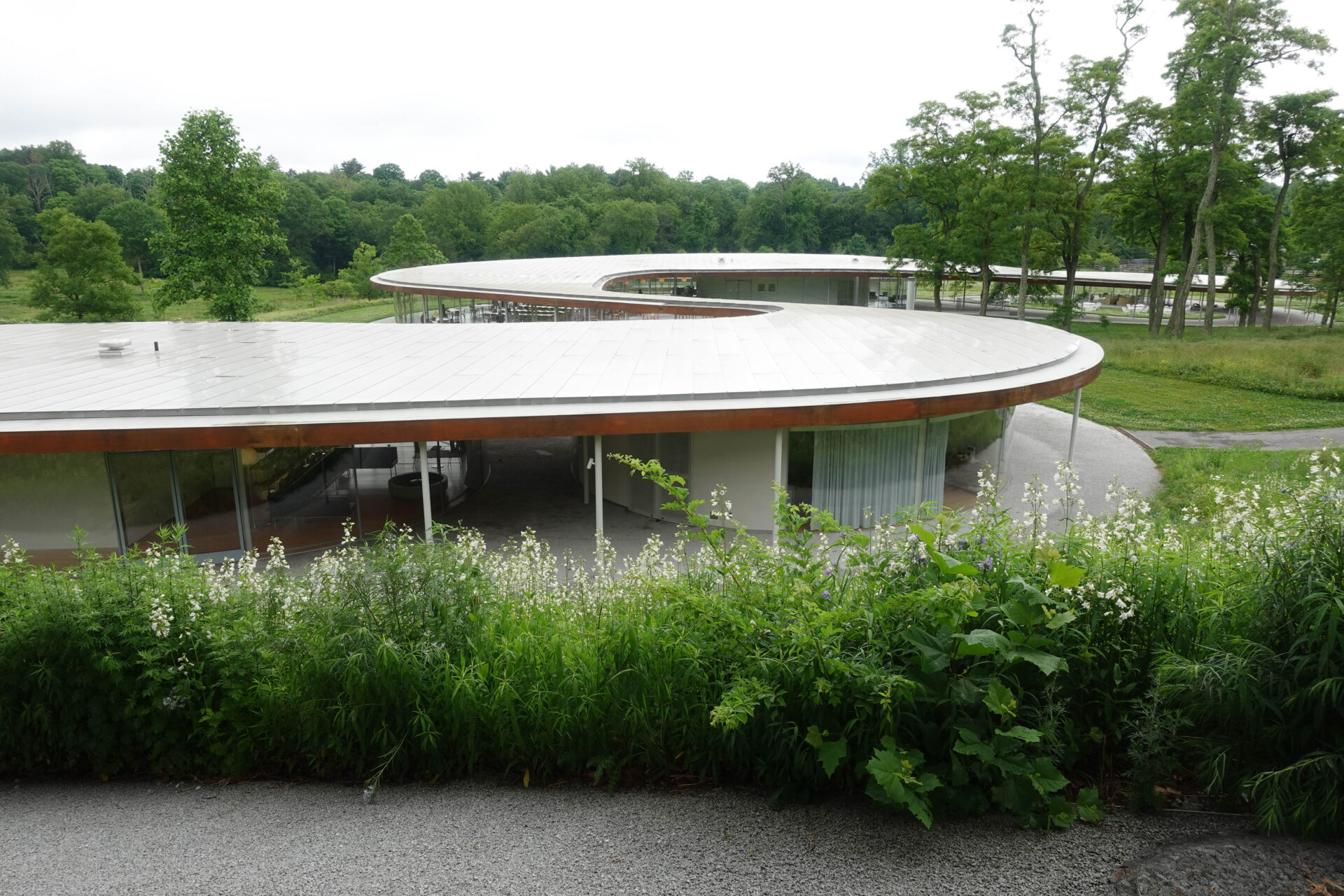

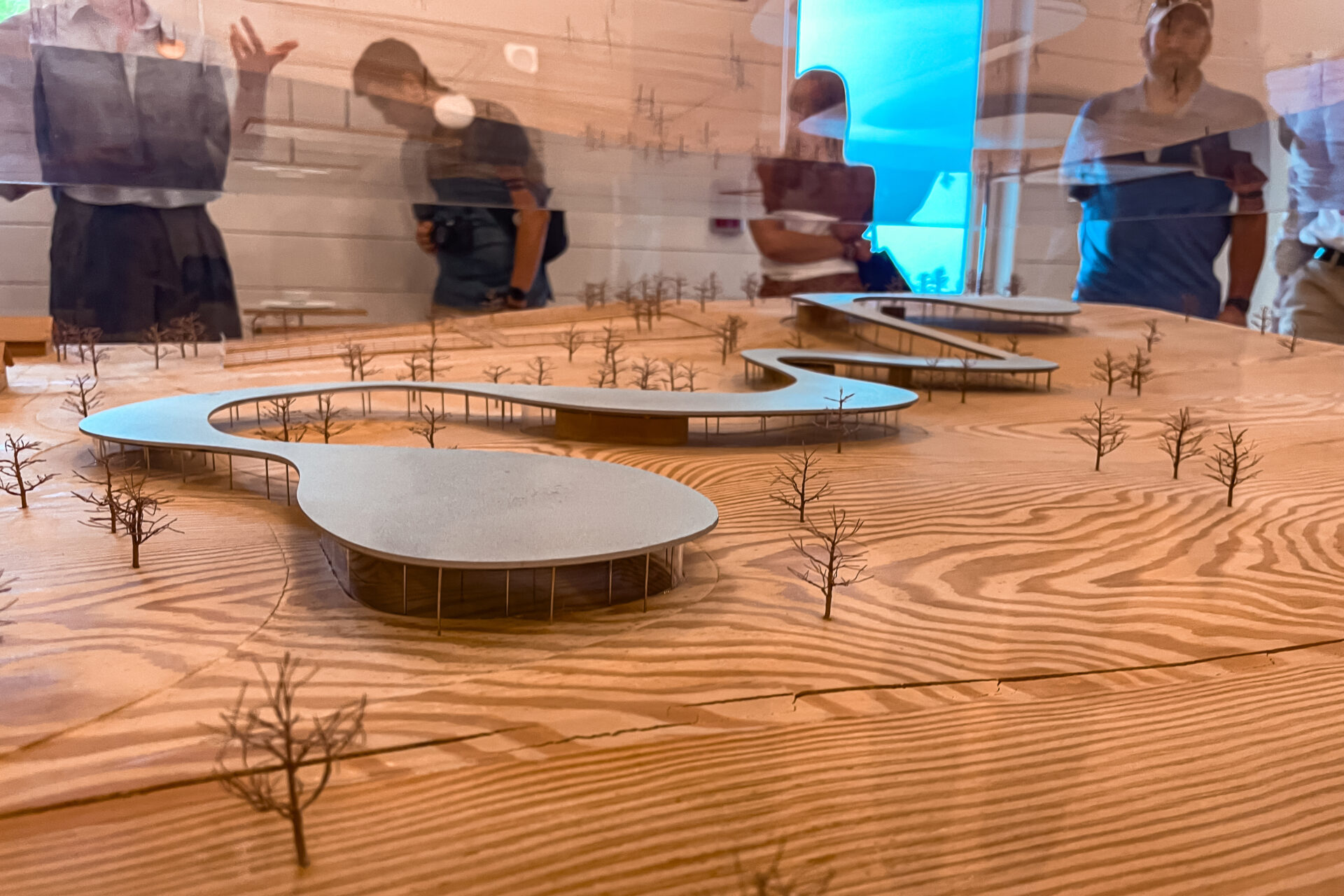

The first stop of our tour was the community center at Grace Farms, designed by Japanese architecture firm, SANAA. Nicknamed “The River,” a glassy, serpentine structure supported by delicate steel columns meanders down a gently sloping hill, perfectly parallel to the contours of the earth. From within the forest of columns you experience panoramic views of the hillside through the glass walls. From the highest point of the structure you see the river of the roof, undulating and twisting its way downward, opaque and moving. The clarity of two opposing ideas of transparency and dynamic solid form is astonishing.

From Grace Farms we moved on to the Eliot Noyes House, where we were greeted by Eliot’s son, Fred, fellow architect and friend of ART, who now owns and cares for the property. The Noyes house is an experiment in indoor-outdoor living. It speaks to concepts of openness, closed-ness, and axial orientation. The plan is a rectangle, organized on an 11-foot module, five modules wide and roughly nine deep. The living and sleeping spaces occupy two parallel sides of the square, connected by covered outdoor passages, forming an open court in the center. The front and back walls of the house are solid stone, while glass contains the living spaces on one side of the square, opening views to the interior court and side yard. The effect of this is total transparency in one direction and total opacity in another. We think of courtyard houses as part of Spanish colonial architecture or typical of warm climates. But according to Fred, who grew up in this house, scampering from one side of the house to the other in the wintertime was no big deal. We can have true indoor-outdoor living here in New England.

Another of the modernist gems of New Canaan, which unfortunately we did not visit on this trip, is Philip Johnson’s Glass House, built a few years before the Noyes House in 1949. Perhaps the most famous house in the region, the Glass House is an object set down in a field. From the outside, it appears as a transparent box, through which one can look straight through to the landscape beyond. From the inside, you experience panoramic views of the surroundings.

When considering these three buildings, you can’t help but compare them as modern pieces of architecture:

• Johnson’s Glass House is an object in a landscape. It looks outward.

• The Noyes House interacts with its landscape. It mostly looks inward.

• SANAA’s Grace Farms becomes the landscape. It looks everywhere.

ART’s modernist interests

So what does all of this modernism have to do with us? you may ask. While the mid-century modern movement has seen a revival in the last couple of decades, the majority of ART’s work has re-interpreted older classical and New England vernacular models. So why should we care? The short answer is “inspiration.” We are inspired by good design in all of its shapes, forms and eras, and we can learn from anything. Every time we see something we haven’t seen before it helps us expand our understanding of the possibilities. Furthermore, modernism and regional vernacular styles are not mutually exclusive. You can have both! You like the seamless transition from indoor to outdoor, but also the cloak of the shingle style roof? Fine by us, we can do that! Learning to do it well comes from studying those who did it well before.