At the Drawing Board:

Reflecting on old-school architectural skills.

This essay originally appeared in the Summer 2019 issue of Historic New England

Drawings are an indispensable tool in designing buildings. For historians or for anyone interested in architecture, architects’ drawings offer insights into the design process and into the evolution of architectural thought, as well as provide records of buildings that may no longer exist. The Library and Archives of Historic New England contains a treasure trove of drawings of New England buildings and collections of drawings by New England architects from the eighteenth century to the present.

We were thrilled when Historic New England accepted our offer of the archives of our firm Albert, Righter & Tittmann Architects. Included are thousands of drawings, along with other documents. We have so far given documents for 180 projects, built and unbuilt, covering the period from 1969 (when the firm began in New Haven, Connecticut, as James Volney Righter Architects) to slightly beyond 1980, when the office moved to Boston. Another group of projects from the 1980s is soon to follow. We plan to continue transferring materials from the 1990s, when we assumed our current partnership, Albert, Righter & Tittmann Architects, and onward.

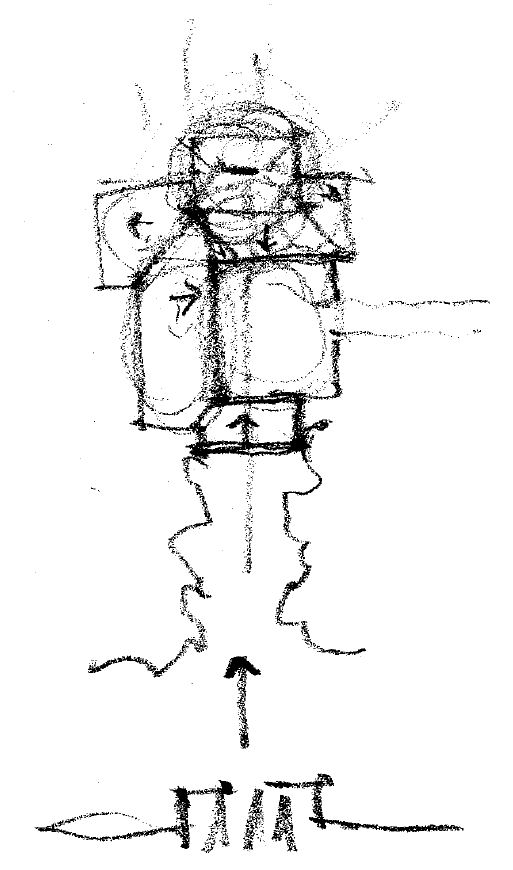

Architectural drawings fall into several categories and serve different purposes. The earliest drawings in a project are rough diagrams with which we try out relationships of rooms to each other and to the site. Next, still in rough sketch form, the diagram takes shape as a building, in three dimensions. At this stage many aspects of the design—the experience of arriving at and moving through the building, how daylight is admitted, and what the flavor and materials of the building may be—are in our heads but not necessarily intelligible to others. Subsequent drawings allow us to get these ideas down on paper and show our clients. We later move from sketch form to drafted drawings, showing at each step more detail, for presentation to regulatory bodies, for pricing by contractors, and finally for construction. We often revert to freehand sketches, even during the construction process, to work out details that need further consideration.

Each type of drawing has its own interest. However, as we look back over drawings we’ve done we’re most strongly attracted to the early sketches, which reveal the germ of an idea. Even in our more developed presentation drawings, such as John Tittmann’s watercolor interior perspective, we try to capture the spontaneity and unselfconsciousness of the early sketches to convey the mood of the building.

Our archives, beginning with work from the mid-1990s, also contain untold megabytes of computer drawings, which are what we spend by far the most time on today. Nonetheless, we still start designing every project by hand. As partner JB Clancy says, the hand is an extension of the brain. The computer seems to put the drawing at a farther remove from the brain. Those of us schooled in hand drawing feel that this is a loss, though a younger generation may find new opportunities in computers.

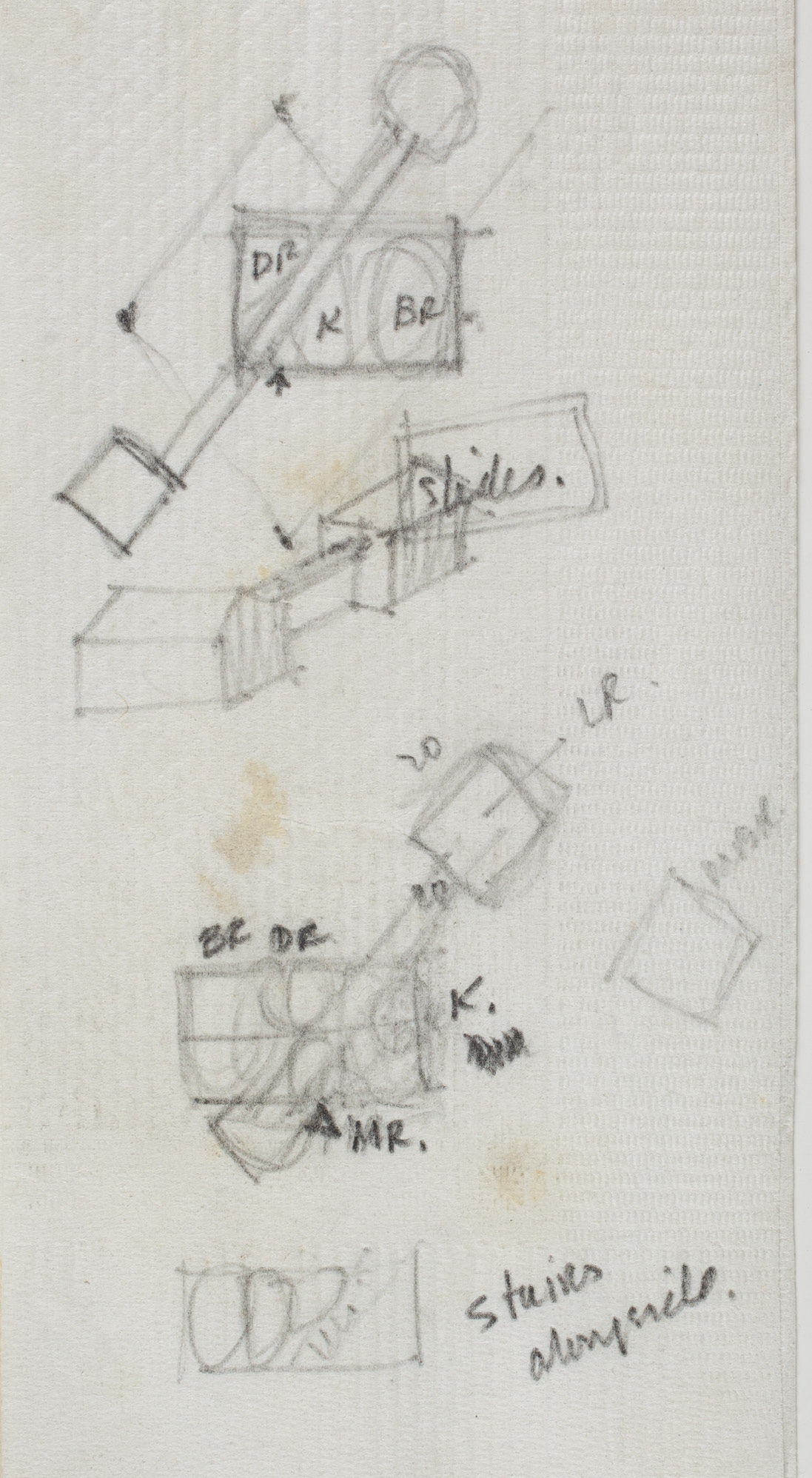

The first soft-pencil doodle for a new house starts in plan as a bubble diagram and begins to take shape as a building. Basic relationships of rooms are established, with thought to the way you move through the site, from cars at the road, through a gateway, into a garden, and through the house toward the water.

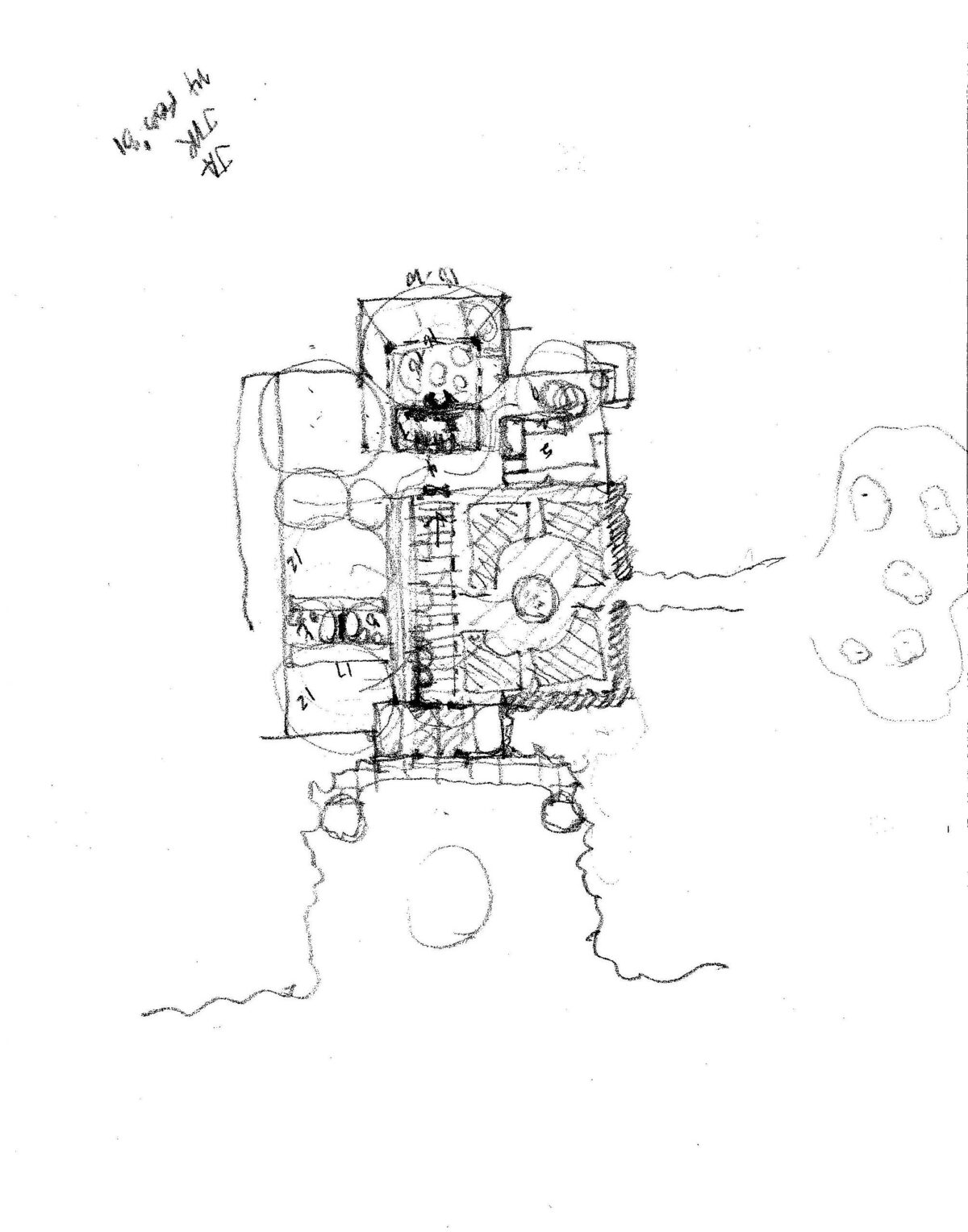

The first soft-pencil doodle for a new house starts in plan as a bubble diagram and begins to take shape as a building. Basic relationships of rooms are established, with thought to the way you move through the site, from cars at the road, through a gateway, into a garden, and through the house toward the water. The diagram takes on more specificity, with further delineation of rooms, furniture within those rooms, and planting in the sheltered entry garden, which is integral to the house that wraps around it.

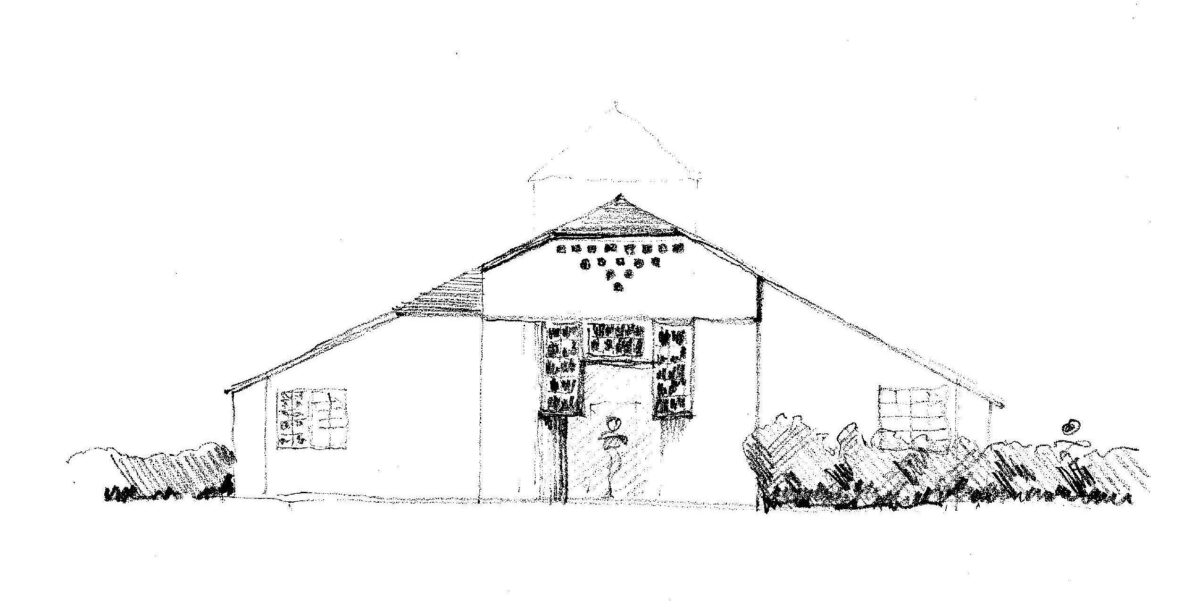

The diagram takes on more specificity, with further delineation of rooms, furniture within those rooms, and planting in the sheltered entry garden, which is integral to the house that wraps around it. The road-facing elevation sketch shows the idea of the “gate lodge,” which centers an otherwise asymmetrical composition, gives more presence to a small house, and enhances the experience of moving from public toward private spaces. References to the American Shingle Style blend with nods to Edwin Lutyens, whose work was receiving renewed attention with an exhibition at the Hayward Gallery in London at the time of this design (1981).

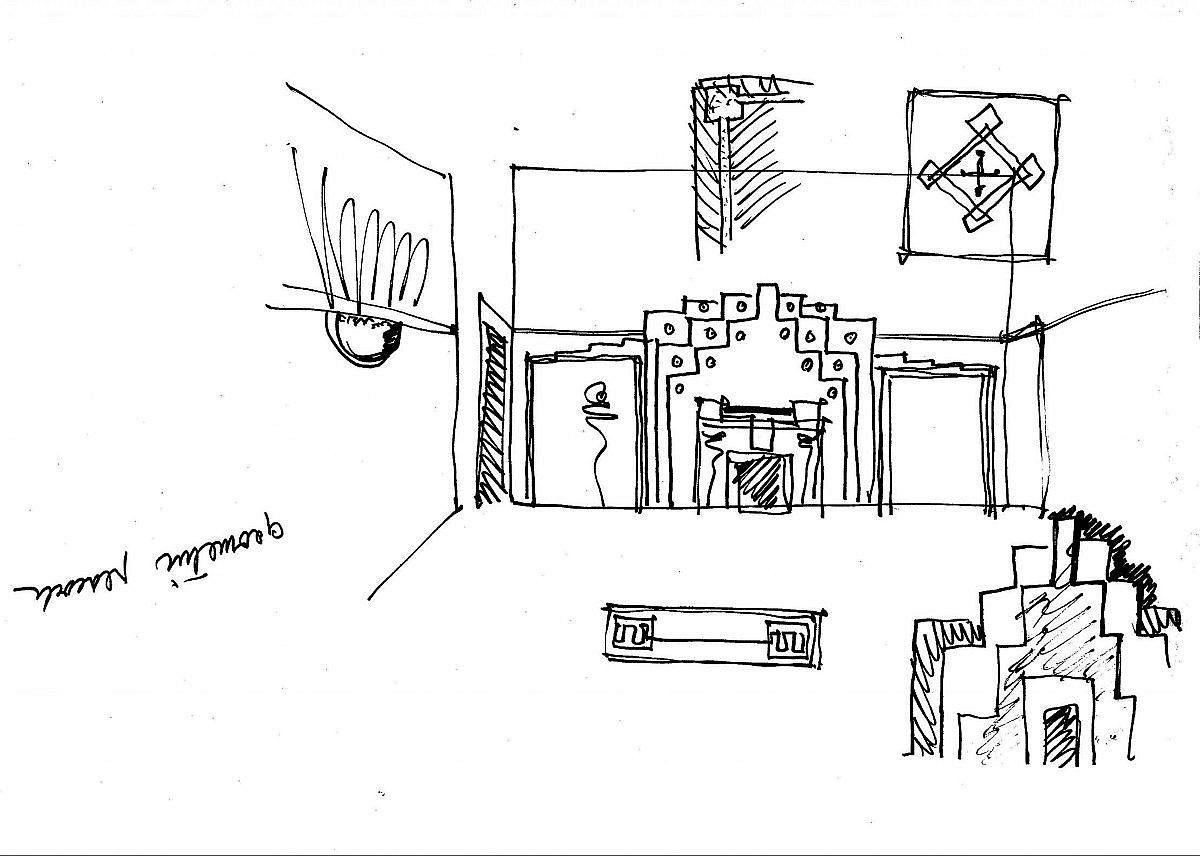

The road-facing elevation sketch shows the idea of the “gate lodge,” which centers an otherwise asymmetrical composition, gives more presence to a small house, and enhances the experience of moving from public toward private spaces. References to the American Shingle Style blend with nods to Edwin Lutyens, whose work was receiving renewed attention with an exhibition at the Hayward Gallery in London at the time of this design (1981). An early perspective sketch of the living room explores decorative possibilities. The note “geometric peacock” (which appears upside down) is a search for a metaphor on which to base the design.

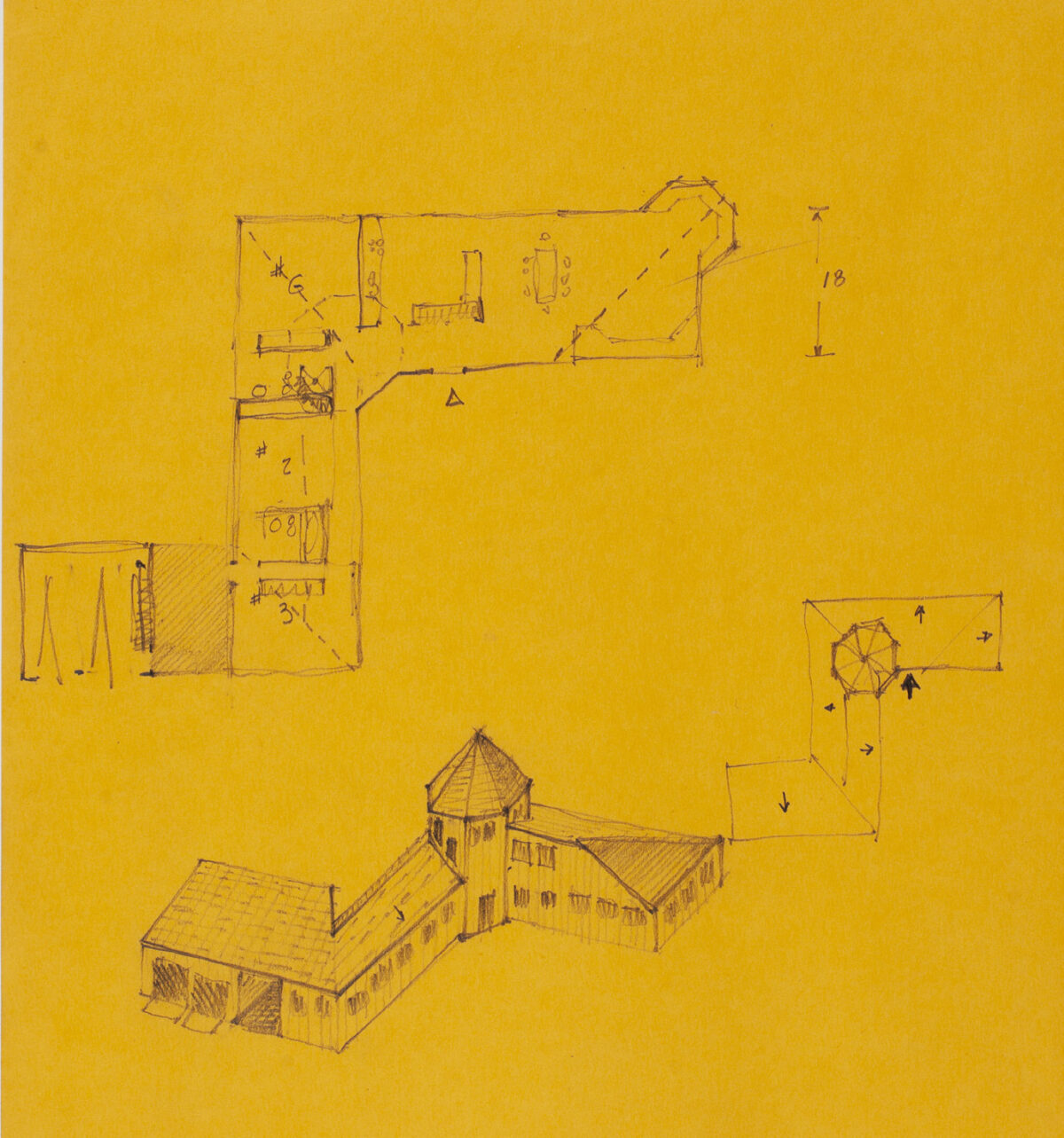

An early perspective sketch of the living room explores decorative possibilities. The note “geometric peacock” (which appears upside down) is a search for a metaphor on which to base the design. A floor plan, roof plan, and thumbnail bird’s-eye perspective on one page describe an early scheme for a house that pinwheels around an octagonal tower. The barn-like vernacular of the design incorporates a reference to the turrets of our client’s grandparents’ Victorian seaside house that had been lost to fire. As with most of our work, the roof plan is a key to figuring out how the design works in three dimensions.

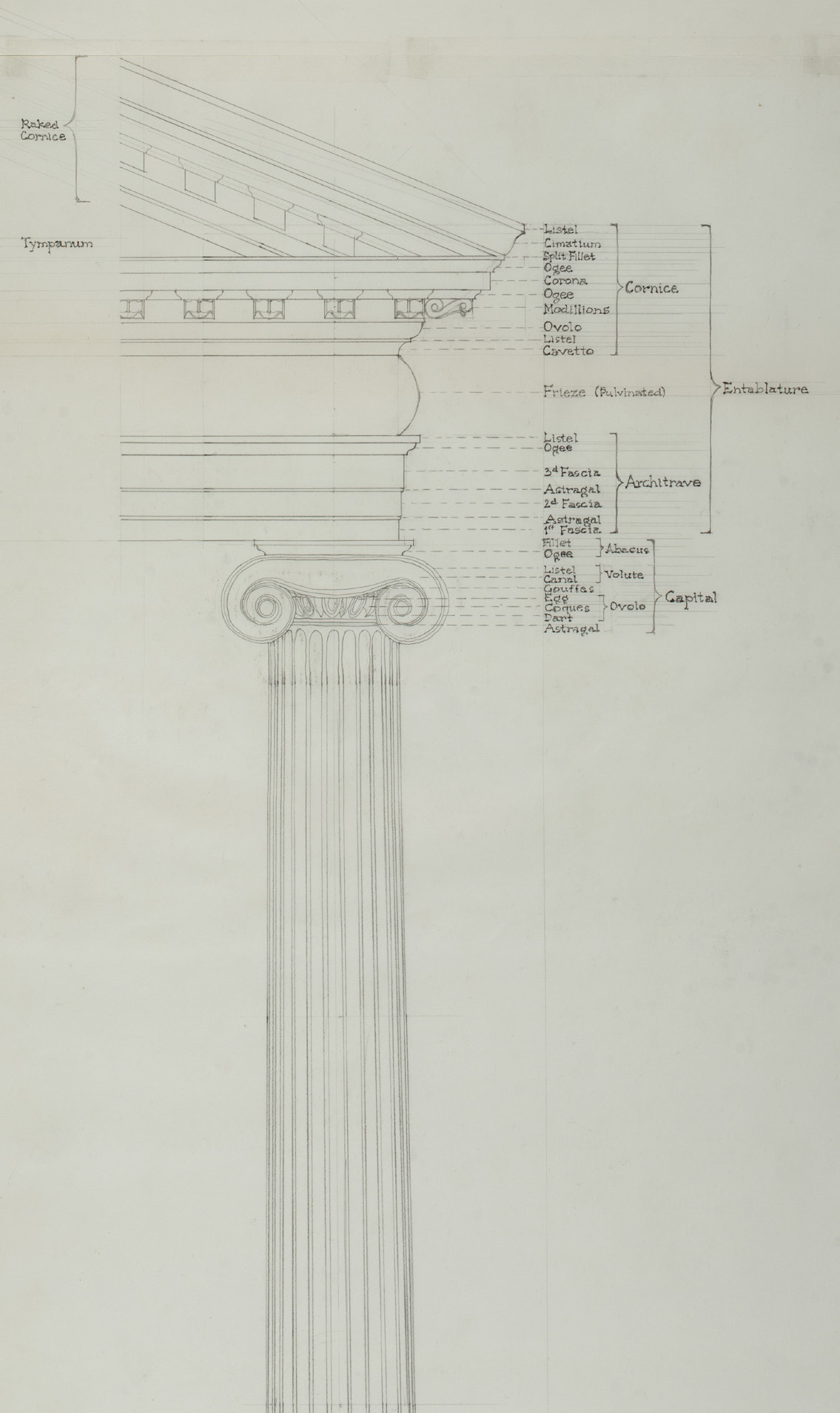

A floor plan, roof plan, and thumbnail bird’s-eye perspective on one page describe an early scheme for a house that pinwheels around an octagonal tower. The barn-like vernacular of the design incorporates a reference to the turrets of our client’s grandparents’ Victorian seaside house that had been lost to fire. As with most of our work, the roof plan is a key to figuring out how the design works in three dimensions. In the late 1970s we, along with others, were excited to discover the Classical tradition, which had been suppressed in architectural education in the post-World War II period. We set out to educate ourselves by studying and drawing the Classical Orders and putting names to all the parts and pieces.

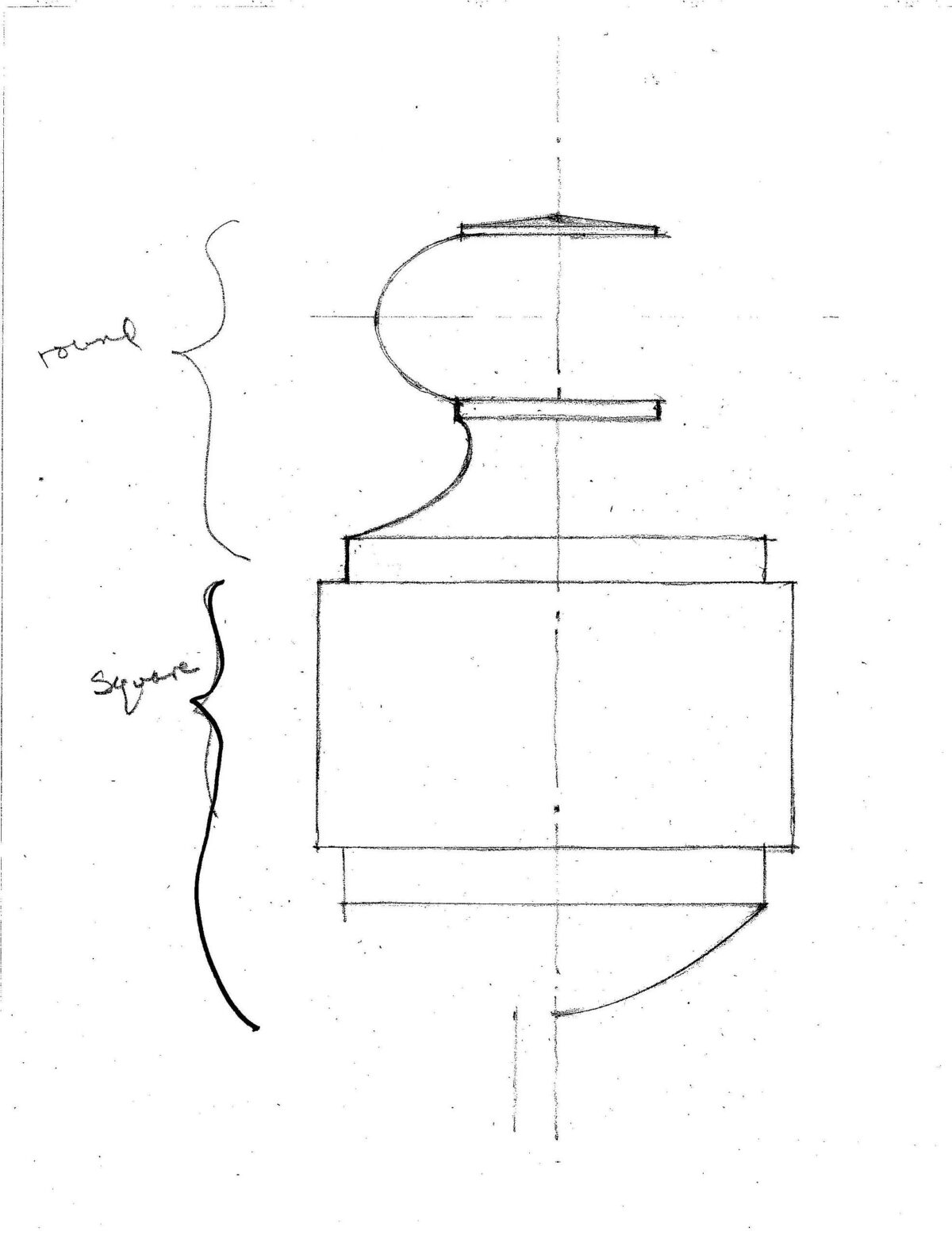

In the late 1970s we, along with others, were excited to discover the Classical tradition, which had been suppressed in architectural education in the post-World War II period. We set out to educate ourselves by studying and drawing the Classical Orders and putting names to all the parts and pieces.  This study, which has continued over the years, gave us fluency in the use of moldings such as the detail sketch of the top and bottom of a stair newel post. The sketch is a kind of shorthand on the way to a more complete drawing.

This study, which has continued over the years, gave us fluency in the use of moldings such as the detail sketch of the top and bottom of a stair newel post. The sketch is a kind of shorthand on the way to a more complete drawing. An interior perspective sketch gives clients a sense of how they might live in a room. This one was part of a series that presented, with watercolor, alternative color schemes.

An interior perspective sketch gives clients a sense of how they might live in a room. This one was part of a series that presented, with watercolor, alternative color schemes.  Ideas can come at the lunch table as well as at the desk, and paper napkins are there to record them.

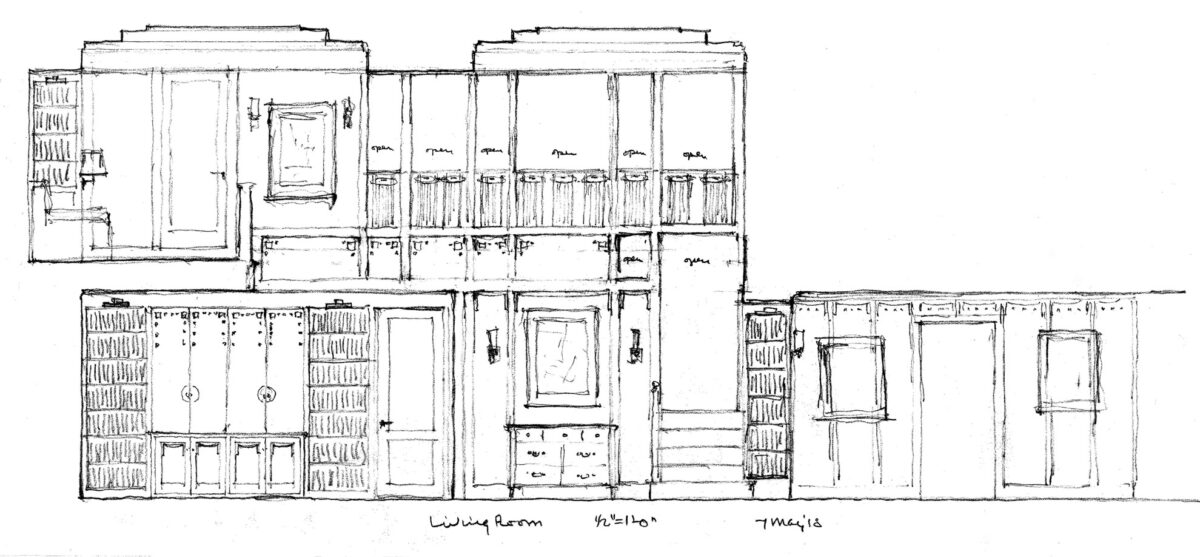

Ideas can come at the lunch table as well as at the desk, and paper napkins are there to record them.  An interior elevation helps us figure out how to make a coherent composition of the various elements—doors, windows, or stairs—on each wall. For this renovation of an apartment with a high living room we introduced a grid in which some of the sections are solid wall panels, some are cabinets or bookshelves, and some are open to a partially concealed stairway.

An interior elevation helps us figure out how to make a coherent composition of the various elements—doors, windows, or stairs—on each wall. For this renovation of an apartment with a high living room we introduced a grid in which some of the sections are solid wall panels, some are cabinets or bookshelves, and some are open to a partially concealed stairway.