What makes Island Architecture?

Conversation on style between North Haven's buildings

A Sense of Place

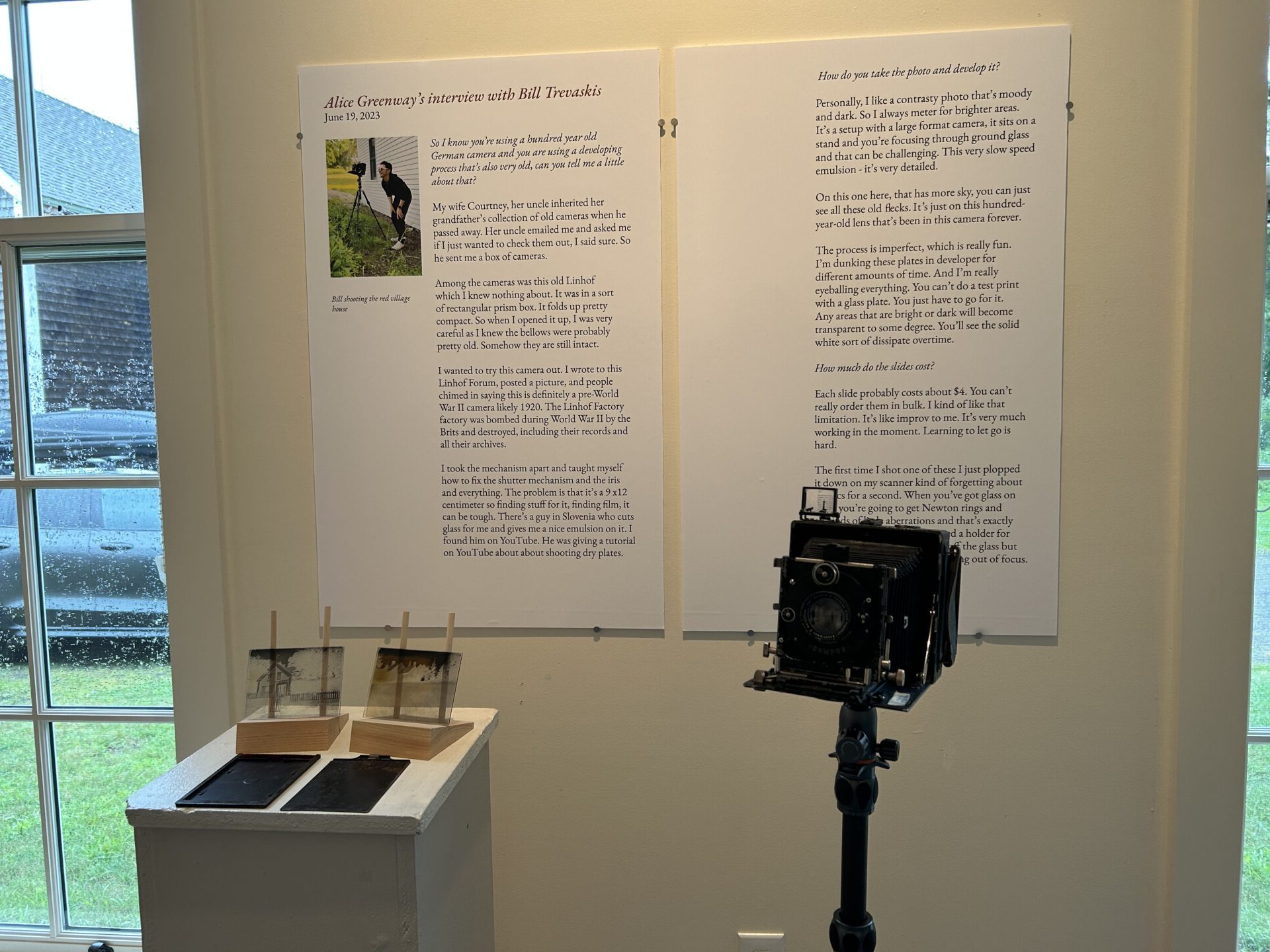

This July, in North Haven, Maine, we held an exhibit that interwove the architectural history of the island and our firm’s work in response (30+ projects over the last four decades). We worked with the North Haven Historical Society and local photographer Bill Trevaskis and considered both North Haven and the north side of Vinalhaven, two islands in Penobscot bay separated by a narrow, protected thoroughfare.

Jacqueline Curtis, the Historical Society director, approached me last summer about this exhibit. I have been going at least once a year with my family since the 90’s and designed the Historical Society’s building back in 2007. She told me of her interest in an exhibit on the island’s built history, wanting to show how new architecture can be responsive to place and feel like it belongs.

The exhibit would also provide a broader vocabulary for people to talk about what is already part of the island’s architecture, and what might come next. This is all very important with imminent sea level rise and other challenges on the horizon, and new infrastructure needing to be built in response.

Beginning this spring, we gathered archival materials from the historical society among other sources, as well as collecting from our own architectural portfolio to tell a story about the interaction between the natural landscape, cultural history, and the constructed environment. Our goal was to convey that when buildings align with their surroundings, a sense of place emerges.

This sense of place is delicate, easily diminished or enhanced by the architecture we create. To understand North Haven, we examined three phases that shaped its architectural identity:

1. Farmhouses & Barns: The Wabanaki Confederacy / French alliance faltered after 150 years of warfare, English people first pushed north and west into Penobscot bay in the 1760s to form permanent communities, building, in the 1780s, the island’s oldest standing buildings. This lays the foundation for the architectural conversations. Indigenous architecture, seasonal structures, did not last.

2. The Greek Revival Village: In the 19th century new forms of economic opportunities beyond farming and the emergence of Greek Revival architecture within the United States added a new design vocabulary to the dialogue.

3. Colonial Revival: Summer residents escaping the heat and smog of rapidly industrializing Boston, buoyed by the wealth extracted from those same industries, sailed north to Maine for the summers. The flexibility offered by advancing building technologies allowed for a wealth of new, artistic housing forms, the first layer of the 20th century contribution to the architectural conversation.

Exploring these chapters of architecture, we used the metaphor of language, recognizing that architectural styles are like distinct dialects, collectively forming our sense of place. Winston Churchill’s words, “we shape our buildings and afterwards our buildings shape us,” capture the essence of this dynamic interaction. Buildings, evaluated for construction, utility, and cultural expression, serve as storytellers across generations.

The Samuel Thomas House exemplifies this journey. Built c. 1760 in Marshfield, MA, the Thomas family, when they left Marshfield in 1784 for the District of Maine, carefully disassembled the home and sailed with it along with a quantity of bricks and rose-headed nails as ballast to the North Island of Vinalhaven (Now north haven). He re-erected his house on Fish Point, just below the great barn beside the towering horse chestnut tree on what is now known as Turner Farm. There the house stood for 220 years, the last 30 of which it was unoccupied and fell into decline. The house was rebuilt on Crabtree Point Road in 2006 as it had been originally constructed now with electricity and plumbing.

Architectural dialogues remind us that buildings are more than structures; they engage in ongoing conversations that influence our shared experience. The exhibit invites us to witness these exchanges, highlighting the delicate balance between preserving the past and fostering innovation. In these conversations, we continue to shape the evolving tapestry of our surroundings.